|

Back

in the fifteenth century,

in a tiny village near Nuremberg,

lived

a family with eighteen children.

Eighteen! In order merely

to keep food

on the table for this mob, the father

and head

of the household, a goldsmith

by profession, worked almost

eighteen

hours a day at his trade and any

other paying

chore he could find in the

neighborhood.

Despite their

seemingly hopeless condition,

two of Albrecht Durer

the Elder's children

had a dream. They both wanted to

pursue

their talent for art, but they knew full

well that

their father would never be financially

able to send either

of them to Nuremberg to

study at the Academy.

After

many long discussions at night in

their crowded bed, the two

boys finally

worked out a pact. They would toss

a coin. The

loser would go down

into the nearby mines and, with his

earnings, support his brother while he

attended the

academy. Then, when that

brother who won the toss

completed

his studies, in four years, he would

support the

other brother at the

academy, either with sales of his

artwork

or, if necessary, also by laboring in the

mines.

They tossed a coin on a Sunday morning

after

church. Albrecht Durer won the

toss and went off to

Nuremberg. Albert

went down into the dangerous mines

and,

for the next four years, financed

his brother, whose work at the

academy

was almost an immediate sensation.

Albrecht's etchings,

his woodcuts, and

his oils were far better than those of

most

of his professors, and by the time he

graduated, he

was beginning to earn

considerable fees for

his

commissioned works.

When the young artist

returned to his village,

the Durer family held a festive

dinner on

their lawn to celebrate Albrecht's triumphant

homecoming.

After a long and memorable meal, punctuated

with

music and laughter, Albrecht rose from

his honored position

at the head of the

table to drink a toast to his beloved

brother

for the years of sacrifice that had enabled

Albrecht

to fulfill his ambition. His closing

words were, "And now,

Albert, blessed brother

of mine, now it is your turn. Now

you can

go to Nuremberg to pursue your

dream, and I will

take care of you."

All heads turned in eager

expectation to the

far end of the table where Albert sat,

tears streaming down his pale face,

shaking his lowered head from

side to

side while he sobbed and repeated,

over and over,

"No ...no ...no ...no."

Finally, Albert rose and wiped the

tears

from his cheeks. He glanced down the

long table at

the faces he loved, and then,

holding his hands close to his

right

cheek, he said softly, "No, brother.

I cannot go to

Nuremberg. It is too late

for me. Look ... look what four

years in

the mines have done to my hands! The

bones in

every finger have been smashed

at least once, and lately I have

been

suffering from arthritis so badly in my

right hand

that I cannot even hold a

glass to return your toast, much

less

make delicate lines on parchment or

canvas with a pen

or a brush. No, brother

... for me it is too

late."

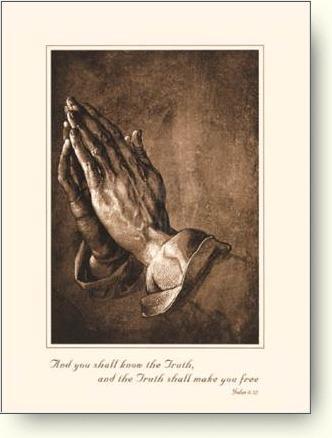

More than 450 years have passed. By now,

Albrecht Durer's hundreds of masterful

portraits, pen and

silver-point sketches,

watercolors, charcoals, woodcuts,

and

copper engravings hang in every great museum

in the world,

but the odds are great that you,

like most people, are

familiar with only one of Albrecht Durer's works. More than

merely

being familiar with it, you very well may

have a

reproduction hanging in your

home or office.

One day,

to pay homage to Albert for all

that he had sacrificed, Albrecht

Durer

painstakingly drew his brother's abused hands

with

palms together and thin fingers stretched skyward. He

called his powerful drawing simply "Hands," but the entire

world almost immediately opened their hearts to his great

masterpiece

and renamed his tribute of love

"The Praying

Hands."

Author Unknown

HOME

|